In 2007, Congress passed the Honest Leadership and Open Government Act, a law designed to curb the influence of lobbyists and slow the “revolving door” of lawmakers cycling from Congress to lobbying firms. Part of the bill prohibited lobbyists from purchasing meals for lawmakers, a meal being defined as food eaten with a knife and fork while sitting.

In 2007, Congress passed the Honest Leadership and Open Government Act, a law designed to curb the influence of lobbyists and slow the “revolving door” of lawmakers cycling from Congress to lobbying firms. Part of the bill prohibited lobbyists from purchasing meals for lawmakers, a meal being defined as food eaten with a knife and fork while sitting.

At the Democratic National Convention the following year, lobbyists threw parties where food was served on toothpicks to standing guests. One even went so far as to serve a rib dish that could be eaten with a specially designed spoon.

The sporking of the American political system by well funded special interests is something Americans have gotten so accustomed to, major media outlets report on fundraising as if they were polls in their own right.

Still, the issue remains important to voters. In a 2018 poll by the Pew Research Center, over 70% of Americans felt people political donors had an outsized influence over government, a feeling shared almost equally by members of both parties.

Despite the popularity of the issue, both major parties have failed to enact any legislation that lobbyists and other special interests couldn’t end run - either by designing their own eating utensil or in the courts. While the Democrats have taken the lead on the issue with their mouths, a quick scan of OpenSecrets.org - a site that reports on campaign contributions and lobbying - revealed every candidate in the 2020 Democratic Primary received some money from industry groups.

Even Marianne Williamson.

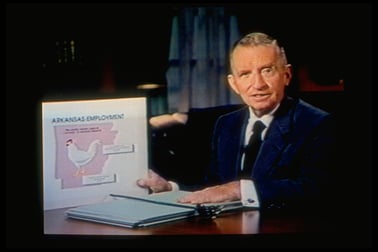

While curbing the donor class’s influence over elected officials has largely been abandoned by the Democrat and Republican establishment, the Reform Party - a party originally founded by Texas billionaire Ross Perot in 1990 - made this a central part of their platform over 20 years ago, and has remained refreshingly consistent on the issue.

I spoke with Chairman-Elect, Nick Hensley, on this week’s episode of You Don’t Have to Yell, to discuss what's happened since the Perot days, the current party platform, and their plans for the coming decade.

You can access the recording below, on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever your bad self gets your podcasts.

Draining the Swamp Before it was Cool

In 1992, both the Democrat and Republican parties had nominated fairly unpopular candidates, those who worked in America’s manufacturing sector had felt the pinch of their jobs moving overseas - accelerated by global trade agreements, and the country had been accumulating debt through years of deficit spending with no end in sight. (Sound similar to any election we might have had in the past four years?)

Ross Perot entered the race first as an independent under a platform that was fiscally conservative, in that he promised to pay down the debt and reduce spending; socially liberal, in that he avoided many of the divisive social issues that alienated people from the Republican Party; and populist, in that he rode the wave of negative sentiment towards both major parties and railed against the influence of outside money on the federal government.

Perot’s platform was one that appealed to “both socially conservative, blue-collar, anti-NAFTA voters with fiscally conservative but socially moderate voters,” helping him win almost 20% of the popular vote - the second third party candidate to crack double digits in a presidential election since George Wallace’s bid in 1968.

It was also a platform that would never have seen the light of day, were it not for Perot’s ability to skirt traditional media by buying up large blocks of ad time to bring his message directly to the public. In effect, Perot got around the need to seek out people who could bankroll his campaign, because he was one of those people himself.

It was also a platform that would never have seen the light of day, were it not for Perot’s ability to skirt traditional media by buying up large blocks of ad time to bring his message directly to the public. In effect, Perot got around the need to seek out people who could bankroll his campaign, because he was one of those people himself.

Perot’s campaign worked so well and turned out to be so popular, that the Commission on Presidential Debates changed their qualification criteria in the following presidential election cycle to exclude him. (Note to third parties: don’t get too popular)

Following the 1996 election, the Reform Party managed to place former Navy SEAL/professional wrestler/actor Jesse Ventura in office as the Governor of Minnesota in 1998 and saw a presidential bid from then businessman Donald Trump, but fell into decline due to infighting and organizational challenges.

Same Platform, Same Problems

If the Reform Party’s platform seems relatively unchanged since Perot first ran in 1992, it’s because American history doesn’t repeat itself, it’s photocopied. The negative sentiment towards uneven trade agreements and mistrust of the political establishment that attracted many voters to Perot only grew in the decades after his bid, and led many to elect Trump as president under a very similar platform, albeit with a little George Wallace mixed in (if you don’t know what I’m talking about, let me Google that for you).

If the Reform Party’s platform seems relatively unchanged since Perot first ran in 1992, it’s because American history doesn’t repeat itself, it’s photocopied. The negative sentiment towards uneven trade agreements and mistrust of the political establishment that attracted many voters to Perot only grew in the decades after his bid, and led many to elect Trump as president under a very similar platform, albeit with a little George Wallace mixed in (if you don’t know what I’m talking about, let me Google that for you).

The Reform Party’s stances have technically been popular enough to win the White House. Their problem, ironically, is money. Without the ability to self-fund a presidential bid Perot had, or the celebrity of Jesse Ventura or Donald Trump, the party isn’t able to gain access to wide swaths of the American public without the help of traditional media.

Hensley’s focus for the coming decade is on grassroots organizing - getting more candidates and volunteers to bring the party’s message to the local level.

An answer also might be found in a 1992 piece Charles Krauthammer wrote of Perot for Time Magazine:

The Perot phenomenon signifies something larger, deeper. It signifies a geologic change in American politics: the growing obsolescence of the great institutions — the political parties, the Establishment media, the Congress — that have traditionally stood between the governors and the governed. The traditional way to achieve and wield power in America is to tame or charm or capture these institutions. Perot’s genius was to realize that for the first time in history, technology makes it possible to bypass them. Win or lose, knowing or not, Perot is the harbinger of a new era of direct democracy.

If Trump proved the Reform Party’s platform wins elections, he also proved a direct to consumer form of campaigning negates the need for support from the press, donors, and even the party establishment. Twitter, Trump’s preferred mode of communication, has made celebrities in their own right, meaning you don’t need decades of being a billionaire or just marketing yourself as one (cough) to build an audience for your ideas.

In this sense, with the ability to gain converts via channels such as Facebook and Twitter, the same direct democracy that created the Reform Party may lead to its rebirth.