When Bravo first launched on cable television in 1980, it was a channel dedicated entirely to the fine arts. At the time, the promise of cable was that networks could rely on subscription revenue to drive their business, meaning they could appeal to niche audiences. The major networks, in contrast, relied on ad revenue and needed to provide more generalized programming to appeal to the widest audience possible.

When Bravo first launched on cable television in 1980, it was a channel dedicated entirely to the fine arts. At the time, the promise of cable was that networks could rely on subscription revenue to drive their business, meaning they could appeal to niche audiences. The major networks, in contrast, relied on ad revenue and needed to provide more generalized programming to appeal to the widest audience possible.

Fast forward 40 years, advertising found its way into cable, and Bravo’s programming schedule has shifted from theater and dance to poorly behaved drunk people fighting on camera.

Some might argue the news has suffered a much worse fate. As with Bravo, what started as a noble mission to bring people news from all over the world 24 hours a day, 7 days a week slowly devolved into a partisan, pundit driven line up of people yelling over each other.

Worse yet, these people can’t blame their behavior on the booze.

The internet has accelerated this process, with smaller, hyperpartisan sites transforming the news industry into one that’s designed to inflame rather than inform

As mentioned in last week’s post on partisan media, where the problem of news once was that we had too little too slow, it’s now become one where we have too much too fast, making it difficult to understand the credibility of a given source and undermining trust in the media.

Arjun Moorthy, this week’s guest on You Don’t Have to Yell, saw the issue of credibility in the media as a serious problem, and co-founded The Factual - a website, newsletter, and browser extension that uses an algorithm to provide readers with an understanding of how credible a given story is, the potential partisan lean, and which important stories we’re missing as we discuss the latest thing to get mad about.

You can listen to the full episode below, on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever your bad self gets your podcasts.

JOURNALISM IN AMERICA - NEVER FAIR, NEVER BALANCED

1787, while the wording of Constitution of the United States was still being debated, Thomas Jefferson said, “Were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers, or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.”

1787, while the wording of Constitution of the United States was still being debated, Thomas Jefferson said, “Were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers, or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.”

After serving two terms as president, Jefferson wrote, “Nothing can now be believed which is seen in a newspaper. Truth itself becomes suspicious by being put into that polluted vehicle.”

Given he wrote the phrase, “All men are created equal” while also actively promoting the institution of slavery, we’ll call this Jefferson’s second greatest contradiction.

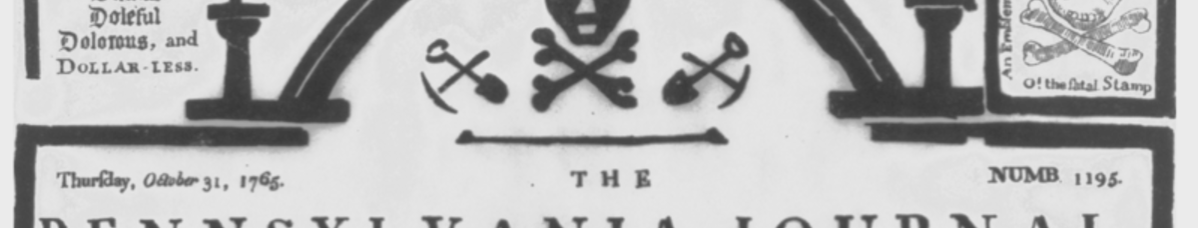

Newspapers had proven vital in the Revolution as a way to unify the population of Colonial America, swaying public opinion in favor of independence and informing them of fighting that often took place days away from their homes, as well as feeding fake news to the British about the progress of the war in the Colonies.. They were also highly partisan, serving as mouthpieces for their publishers and other political interests, and often used sensational stories to boost circulation.

In this sense, the media has always been viewed with a certain amount of suspicion, and has served as much to guide what we talk about as to inform our opinion. What has changed isn’t necessarily media bias or accuracy, but how divergent those partisan narratives are.

An example can be found in how people viewed the Trump Administration’s decision to send federal law enforcement to respond to protests in Portland, Oregon. A study fielded by Data for Progress revealed opinions on whether this was essential to public safety or on overreach of federal authority was split along partisan lines.

Effectively, America is sliding either into autocracy or anarchy, depending on who you ask.

DOES TRUTH SELL?

The fact Americans can’t agree on what kind of existential crisis we’re experiencing is a crisis in and of itself. Democracy requires consensus, and consensus requires issues be discussed from a common point of truth.

What’s changed isn’t the reliability of journalism or lack of partisan lean, but the fact Americans can literally consume thousands of headlines per day from an equal number of suspect sources. With an ad driven media industry rewarded by clicks and shares and platforms such as Facebook delivering stories with the highest number of interactions - positive and negative - our media diet often consists of information that hardens our biases or outright offends us.

This has been a successful model for the media industry in recent years, leading to the question - do people actually care whether their news is credible or not?

In a rare bright spot in 2020, The Factual’s subscriber base delivers a resounding yes. While Moorthy originally expected their audience to be mainly left-leaning folks living in coastal, urban enclaves, he was surprised to find how well received it was by people from across the political spectrum spread across the country.

Roger Ailes, former Chairman and CEO of Fox News said, “People don’t want to be informed, they want to feel informed.” You could argue that modern media has built a business off confirmation bias - the tendency for people to gravitate towards information that justifies their opinions - by delivering content that appeals to a certain partisan lean.

The Factual has revealed a market based on another psychological tendency - the need for certainty. The market rewards what’s rare, and with an oversupply of information and a low barrier to entry as far as what gets published, what’s rare is trust and reliability.

While it’s always risky to bet on people’s better angels, for The Factual, this risk seems to be paying off.

You can sign up for The Factual's daily newsletter at TheFactual.com. This is not a paid promotion - I just really like their mission.