When Ronald Reagan first took office in 1981, America’s chief rival was the Soviet Union - a godless military juggernaut lead by a plucky troupe of septuagenarians intent on freeing the workers of the world from the shackles of capitalism via a mix of forced labor and harsh autocratic rule. I’m sure it seemed like a good idea at the time.

Reagan’s military strategy upon taking office was fairly simple - force the Soviets into an arms race by increasing military spending, and eventually our chief global adversary would bankrupt themselves. While how much Reagan’s military buildup led to the fall of the Soviet Union is still being debated, military spending under Reagan grew from 4.9% of GDP in 1980 to 5.8% in 1988 - the highest since the end of the Vietnam War.

Since World War 2, America’s chief military asset has been the ability to throw billions and billions of dollars at our defense budget without asking questions. There’s no greater evidence of this than in the fact that we're the only world power that’s suggested a military presence in space - a place where there aren’t any people - and that we’ve made that suggestion twice. At the same time, we tend to ask, “Can we afford this?” to every other proposed government expenditure that finds its way into the conversation - such as universal health care, the Green New Deal, or keeping interstate bridges from falling into the Mississippi.

What we rarely ask is, where would these billions and billions of dollars deliver the best return?

On this week’s episode of You Don’t Have to Yell, I interviewed economist Heidi Peltier, Project Director of the Costs of War Project at Boston University. Heidi’s work focuses not only on the economic, social, and environmental costs of American military policy since 9/11, but also on what the return of those same dollars would have been if they were invested in other areas.

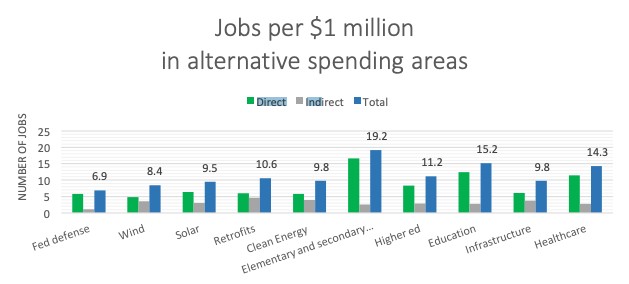

From a job creation standpoint, the defense industry employs the least number of people for each dollar spent. A report Peltier compiled in 2017 showed that, if the US redirected the approximately $230 billion it spends on wars every year to other sectors, it could generate anywhere from 326,000 to 2.6 million more jobs. Keeping in mind an increase of 200,000 is considered “good” in the monthly jobs report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, these numbers aren’t insignificant.

(source: Heidi Peltier, The Job Opportunity Costs of War)

What’s more, a study by the Center for International Policy revealed a plan that could save $1.2 trillion over the next decade without negatively impacting the nation’s defense capabilities. That’s roughly 50% of the proposed cost of the Green New Deal without having to increase taxes or take on more debt.

If we look at the Federal Budget, the military ranks 3rd in total spending, behind Social Security and Medicare. Ranking 4th in total spending is interest paid on the federal debt - which has climbed from $230 billion to almost $400 billion in the last four years. That money does nothing to reduce the total debt owed by the United States and comes at a time of historically low interest rates, so we can only assume those costs will take an even greater portion of the budget with time.

Since Reagan, much of America’s military advantage has been in the ability to outspend our rivals. In financing our budget via deficit spending, we’ve found ourselves in a debtors’ prison of sorts - where we’ll eventually need to choose between low taxes or significant cuts in military and/or civilian programs.

You don’t need to be an economist to find some of the easier places to cut - such as spending $100 million on tanks the military doesn’t want and $34 billion on a plane reported not to work, but not all of our choices will be this easy.

The role our military buildup during the Reagan Era played in the fall of the Soviet Union may be up for debate, but that strategy seems to be working now to bankrupt us. For better or for worse, this time the plucky group of septuagenarians we’re up against are our own.

(You can listen to the episode below, on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you take your bad self to listen to podcasts)